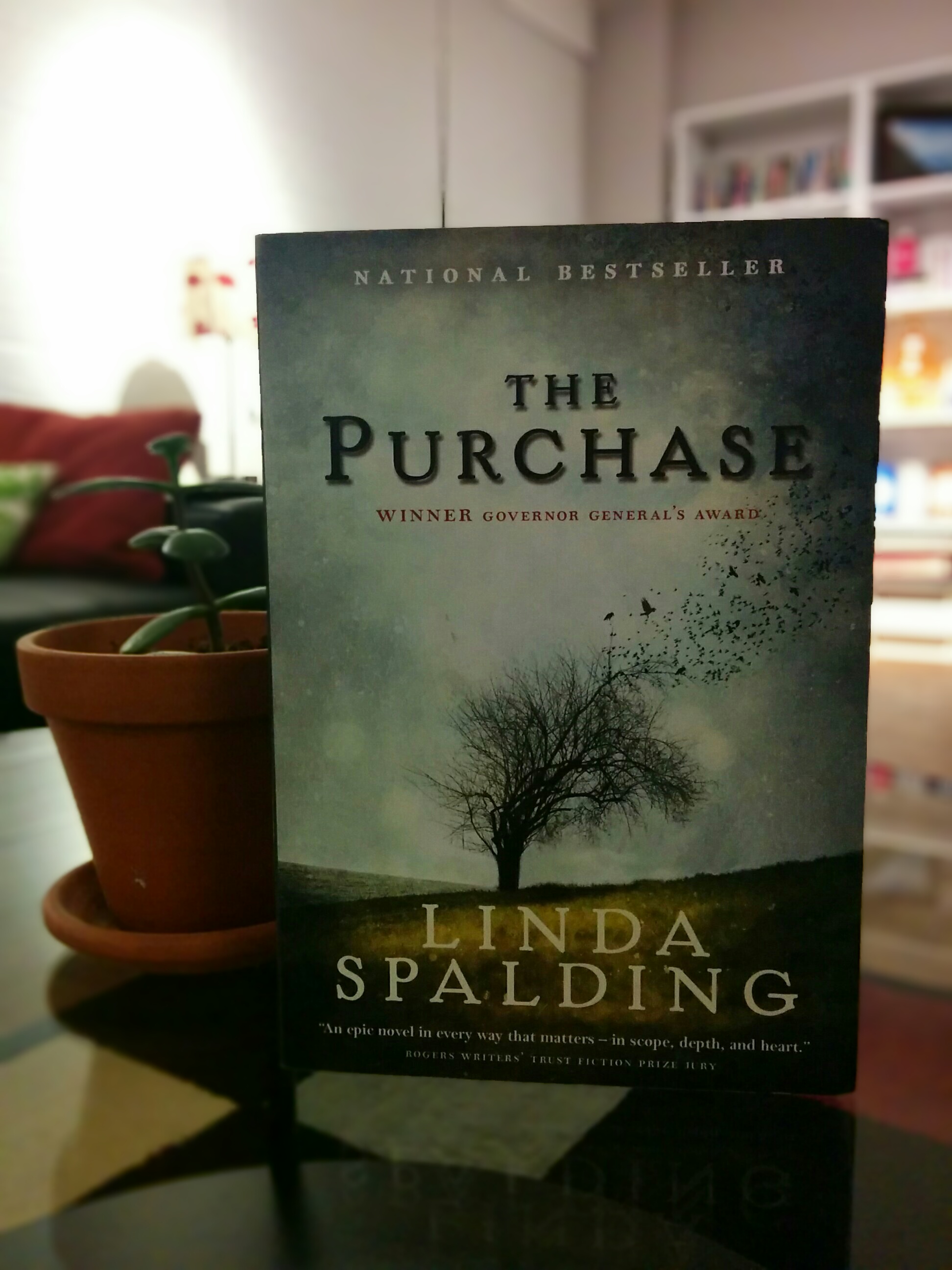

3 surprising things about Linda Spalding’s The Purchase

In: Book review, Books, How to write

Linda Spalding’s The Purchase follows disowned Quaker widower Daniel Dickenson as he brings his family from Pennsylvania to Virginia. It’s the southern US in 1798. Although he means to maintain his abolitionist Quaker ideals, Daniel goes to an auction and pays to enslave a young man named Onesimus, convincing himself that he’ll eventually set the young man free. But surprising and heartbreaking outcomes arise from that purchase, not only for Onesimus, but also for Daniel, his children, and the enslaved workers and enslavers in the community.

I had the pleasure of meeting Linda Spalding at the Banff Centre for the Arts in 2015, and I can’t be surprised she wrote this engrossing book. She is generous in her approach, and this book is generous in its telling. With her non-fiction background, Linda so naturally and convincingly works in research about Antebellum slavery and living and working on stolen land in that period of US history. The Purchase is the best work of historical fiction I’ve read in a long time. Here are three surprising things I learned in the process of reading it.

1. Stories can be both sprawling and claustrophobic.

I do appreciate good epic novels. I’m often amazed by their range and ambition. But since they tend to span many years and characters, I find epic novels can have a distant, even heartless feel. Characters can come across as pawns of a vague global misfortune, and that prevents me from connecting with what they might really feel. The Purchase is one of the only epic-style books I know of that keeps a big scope and still makes me feel like I’m up close. Most of the story happens over a few plots of land, and that’s how the majority of us live, even in this age of planes and trains and automobiles. We’re tied to the same three or four blocks every day. This particularity of place does makes the story feel too close for comfort at times, and it’s actually very suitable. When you think of how people who were enslaved were so penned in and living in the fiery circle of their brutalizers every day, this claustrophobic approach to “epicness” makes the novel really effective.

2. You can mix modern and historical sensibilities in a seamless way.

I admire a writer who can maintain an “old-timey” narration, and I know it’s useful to make a historical story feel more authentic. But reading that kind of narrative pitch over hundreds of pages, added to old-timey dialogue, can be a total pain even if it is appropriate to the story itself. So I did panic a little when I read this early on:

“Thee shall cause scandal by keeping the servant girl in thy house,” his father admonished. “Thee must find a proper mother for thy orphans.”

“Admonished” and “thee” in one sentence. I wasn’t certain I how long I’d last. But I found that the author did wonderful work marrying an old and new feel throughout the book. Beyond her choices in language, I think the modern approach I could connect with came in strategic moments where she explored state of mind and feelings in a way a real old-time book probably wouldn’t have.

3. Motives, even the important ones, don’t always have to be known.

At the same time, there are moments in The Purchase where character motives weren’t explained. Reading some of the reviews on Goodreads, I noticed a few readers had a negative reaction to that. The author never explains why so-and-so did this-and-that and I just couldn’t buy into it … I get where that comes from. I can guess at a character’s motivation but I often want the author to somehow confirm the correctness of my guess. Is that too much to ask?

But why do people do what they do? And should the author always hand it over to us so plainly? Does it help us get any closer to a character who, say, deludes themselves or doesn’t understand why they do what they do either? And do we even believe the author when she finally does hint at the answer?

Right at the start of the book, it’s a mystery why Daniel would marry Ruth, a Methodist orphan girl, when he knew the Quakers would shun and force him out of the only life he and his children knew. That was the decision that set them down a compromising road that led to such misery and loss. Was it a lapse in judgement? Was he really concerned about the poor orphan’s fate? I kept searching for an answer and found nothing helpful until the end of the book:

Thee must find a proper mother for thy orphans, his father had said, and Daniel ached for Ruth Boyd, although he turned from her now …

(Notice how it’s connected to the sentence that made me nervous at the start.) I find the word “ached” so interesting here. Was it that simple? That Daniel wanted this girl hardly older than his daughter, probably desired her in an unseemly way? And once he made his decision, he had to justify it to himself and others to make it something nobler? I tried to rewrite his motives into something more but kept returning to “ached”. Not “hoped” or “needed” or anything like that. It seems like an intentional choice on the author’s part. How does a reader deal with such an unwise, awfully human motivation? What else is a reader to feel but disturbed and upset?

The Purchase is a fantastic read and useful to learn from. For me, those traits make for an ideal story that I’ll always keep coming back to.

you might also like

-

Reading Now: The Persuaders

June 17, 2023

-

Novel Writing Recipe, Part 1

May 28, 2019

-

How All My Puny Sorrows showed me I’m a puny writer

February 17, 2016

0 comments

Leave a comment

Leave a Reply